MINING LIBRARY TREASURES 2022

Road trip through Italy, except it is 400 years ago.

Click here for an interactive exploration of this book!

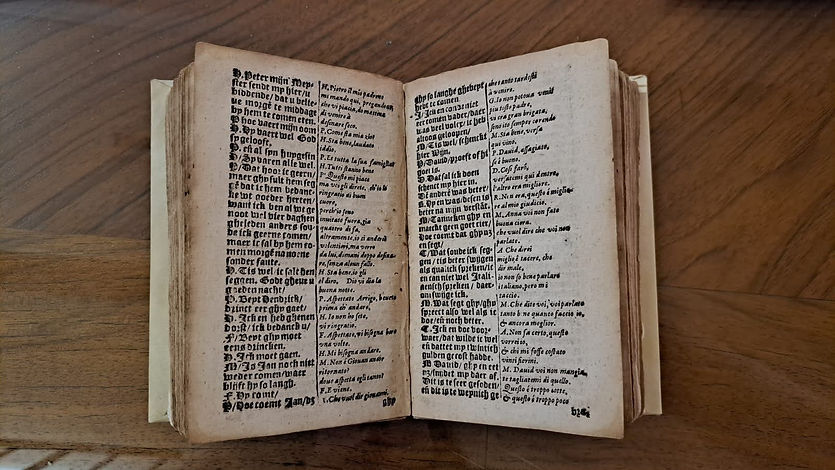

The Delitiae Italiae is a seventeenth-century travel guide to 38 Italian cities. The guide was originally written in German by Georg Kranitz von Wertheim in 1599 but was translated into Dutch by Caspar Ens. The first Dutch Delitiae Italiae was published in 1602 by Jan Janszoon in the Dutch city of Arnhem under the full title: Delitiae Italiae: Eyghentlijcke beschrijvinge wat door gantz Italien in elcke stadt ende plaets te sien is van antiquiteyten, palleysen, piramyden, lusthoven, begraffenissen ende andere ghedenckweerdighe dingen. However, a slightly younger edition of this book from 1609 can be found at the KNIR, with the specific collation: 8: A8, B-I8, K-P8, Q4. It is this work that this essay will analyse further.

Firstly, it would be useful to introduce the historical and cultural context in which the Delitiae Italiae was published. The Delitiae reflects a trend of growing interest in travelling and travel literature in the second half of the sixteenth century. There had long been a tradition of European travel from the Middle Ages onwards, but these journeys usually centred around religion or trade. This started to change during the sixteenth century when the humanists advocated a new purpose for travel: education and personal development. This new intention for travel can be traced in the Delitiae as well and as such this guide becomes a reflection of new humanist ideals of education. For example, the Delitiae describes each town not only in terms of cultural and historical richness but also in terms of political and economic reality, so that the new elites that will one day take on important occupations could educate themselves on such matters.

Then, there is also the textual dimension of the book. The Delitiae was written as a travel guide to Italy. The route starts in Venice and includes many Italian cities which continue to welcome countless foreign visitors today such as Bologna, Florence, Rome, Naples, Milan, and Florence. The book contains a lot of user-oriented travel information such as currency exchange rates, how and for what price to arrange transportation and at which inns one could stay the night. Thus, the book was written with a very practical outlook on travelling and was, therefore, in all likelihood, meant to be taken along with the traveller on their journey. In many ways, then, we could compare the Delitiae Italiae to our modern-day Lonely Planet’s, which serve much the same purpose and contain similar information, albeit adapted to the needs of travellers in the twenty-first century. Consequently, this book functions as a practical object, rather than ‘high literature’, not meant to preserve, but to be used in daily life.

Another indicator of this is that the Delitiae was published in an octavo format, which we would now regard as ‘pocket size’. This meant that it was easy to carry around whilst on the move. What is striking, however, is that the book does not contain any sort of annotation, such as underlinings or marginalia, which would undermine the argument of its practicality since it shows no traces of it ever having been used in such contexts.

As for the user, there are several indicators that the guide was aimed at a Dutch audience. The most obvious proof lies in the fact that the book was translated into vernacular Dutch, and was thus aimed at a Dutch-speaking audience. Secondly, the end of the guide provides the reader with comprehensive Dutch-Italian dialogue translations, useful only to speakers of Dutch. Furthermore, the font in which the work was printed — the Gothic minuscule — was typically used by Northern European publishers, specifically in Germany and the Netherlands. The use of Gothic script implies a conscious choice to adhere to the Northern European printing tradition that the audience was familiar with.

Another interesting textual and material aspect of this version of the Delitiae Italiae is that it is bound together with another travel guide: the Delitiae Galliae & Angliae. This work, which begins a little past halfway through the book, contains travel information about England and France of a similar scope to that presented in the Delitiae Italiae. Both works, therefore, could be used as a guide to conduct a ‘grand tour’. The grand tour was an educational journey for men of the elite that formed a transition period between youth and adulthood and that would prepare the men for their future occupations. By binding the two works together, the compiler has asserted a strong and complementary relationship between them and stimulates the reader to read both works as though they were one. This in turn invites the reader to partake in travels to all three countries for their grand tour. Whether this was the true ambition of the compiler is a challenging — if not impossible — question to answer. However, this intention seems plausible since both France and Italy were acknowledged grand tour destinations. Another reason why the two books were bound together could be that they were both translated by the same person, that is, by Caspar Ens. Consequently, the related contents of the two works and the fact that one person worked on both texts may have resulted in their intertwining in one binding.

For present-day uses, the Delitiae Italiae allows us to learn about how people viewed and experienced journeys to Italy in the seventeenth century, what sights they thought were important, and what cities were worth visiting for intellectual enrichment. The guide does so by providing insight into contemporary local customs, religious practices, and folklore. Furthermore, works of this kind form a valuable source of textual discourse for historical linguists to help trace the history of the Dutch language. Combining that with the historical and material dimensions offered by this work, it is not hard to argue that the Delitiae truly is a travel treasure.

Written by Fleurien Drop.

Fleurien Drop is currently doing a Bachelor’s in English Language and Culture at Leiden University. She was a part of the editor’s team for this project and as such has helped people to improve their essays linguistically.

Title: Delitiae Italiae, dat is, Eyghentlijcke beschrijvinghe, wat door gantsch Italien in elcke stadt ende plaets te zien is / G.K.V.W.

Author: Caspar Ens

Publisher: Jan Janszn. (Arnhem)

Date of publication: 1609

KNIR copy: Pregiato Octavo DR S8 (1)

Description: [8], 164, [74]p, ; 15 cm. (8vo).

References

José van der Helm, Roos Hamelink, and Geertje Wilmsen, Delitiae Italiae : een reis door het zeventiende-eeuwse Italië. (Hilversum: Uitgeverij Verloren, 2021)

José van der Helm, Instructions for learning Italian in two early-modern Dutch travel guides: Delitiae Italiae (1602) and Delitiae Urbis Romae (1625)’. (Igitur publishing, 2014)

Eddy Verbaan, ‘Reismethode’ in De woonplaats van de faam : grondslagen van de stadsbeschrijving in de zeventiende-eeuwse republiek. (Hilversum: Uitgeverij Verloren, 2011). Retrieved from https://hdl.handle.net/1887/18256